360° Financial Trend Detection

360° Financial Trend Detection

There’s a change coming to the U.S. retirement system in 2026. It’s been framed as a technical adjustment, a nudge toward a supposedly superior savings vehicle. But when you strip away the jargon and run the numbers, it looks less like a helpful nudge and more like a targeted removal of a valuable tax arbitrage opportunity for a specific class of American saver: the diligent, high-earning, late-career professional.

Starting January 1, 2026, a rule embedded in the SECURE 2.0 Act takes full effect. If you are 50 or older and earned more than $145,000 in the prior year, your ability to make pre-tax "catch-up" contributions to your 401(k) will be eliminated. This Tax break for high earners over 50 to disappear in 2026 means that extra $7,500—or $11,250 for those aged 60 to 63—that you could previously use to lower your current taxable income must now be directed into a Roth 401(k) on an after-tax basis.

Let's be precise about what this means in dollar terms. For an individual in a combined federal and state tax bracket of, say, 37%, the loss of a $7,500 pre-tax contribution translates to an immediate tax increase of $2,775. For those eligible for the "super catch-up," an $11,250 contribution in that same bracket represents a lost deduction worth $4,162.50. This isn't a minor tweak. It's a significant shift in the tax liability for people in their peak earning years.

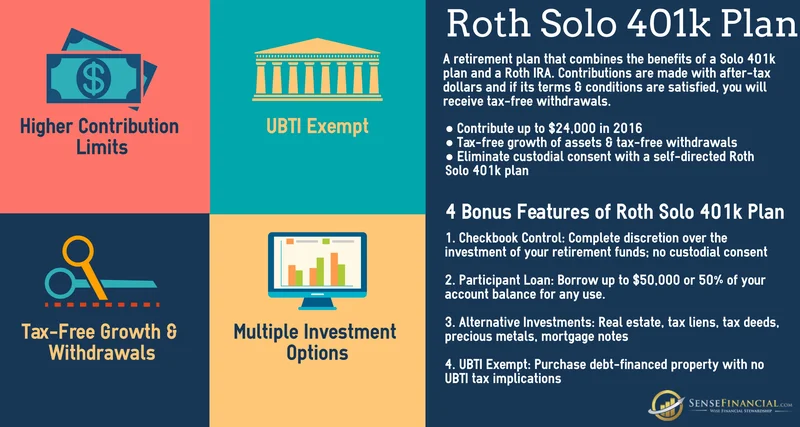

The official narrative spun by proponents is that this is, ultimately, for the saver's own good. Financial advisors are quoted explaining the long-term benefits of tax-free growth and withdrawals from a Roth account. They call it "delayed gratification." And this is the part of the report that I find genuinely puzzling—the framing of a government mandate as a piece of benevolent financial advice. The argument presupposes that the government has a clearer view of your personal tax trajectory than you do. Is that a reasonable assumption?

The entire "pre-tax versus Roth" debate hinges on one unknowable variable: your effective tax rate in retirement versus your marginal tax rate today. The conventional wisdom is to contribute pre-tax when your income (and tax rate) is high and withdraw in retirement when your income (and tax rate) is presumably lower. The Roth strategy is the inverse. Forcing high earners into Roth catch-up contributions is an implicit bet by the government that your tax rate will be higher in the future.

Maybe it will be. But maybe it won’t. It’s a personal calculation based on expected retirement income, location, and, most critically, future congressional tax policy. To remove the option of making a pre-tax contribution is to remove a key strategic lever from the hands of the saver. It's like a mechanic telling a driver they can no longer use second gear because fourth gear is more efficient on the highway. It’s a nonsensical restriction that ignores the varied terrain of an entire financial lifetime.

The data shows this isn't a universal tool anyway. According to Vanguard, only about 16% of eligible savers made catch-up contributions in 2024. So, we're not talking about a broad-based behavioral shift. We're talking about a feature used by a relatively small cohort—about one-in-six eligible participants, to be more exact, 16%—who tend to be higher-income and more engaged with their retirement planning. These are precisely the people who are most likely to be making a deliberate, calculated decision about their tax strategy.

Now, let's look at the real motivation. The U.S. government is facing a national debt exceeding $37 trillion. This rule change is a classic accounting maneuver. (It’s a common tactic in legislative budgeting, known as a timing shift.) By forcing contributions into Roth accounts, the Treasury collects tax revenue now instead of 10, 15, or 20 years from now. It shores up present-day balance sheets by pulling forward future tax receipts. It’s a convenient solution for politicians, but it comes at the direct expense of the saver’s flexibility.

The most glaring flaw in this entire scheme, however, is operational. What happens if an employee’s 401(k) plan doesn’t offer a Roth option? The law is clear: that employee is then barred from making any catch-up contributions at all. This isn't a nudge; it's a cliff. While most large plans have a Roth component, a non-trivial number do not. Data from Vanguard suggests 14% of their plans lack a Roth option; for Fidelity, it’s 6%. Are we really prepared to tell a 58-year-old executive at one of those firms that their ability to save an extra $7,500 a year has simply vanished due to their employer's plan design? It's a punitive and poorly conceived consequence.

Let’s call this what it is. This is not a benevolent policy designed to optimize American retirement outcomes. It is a cash grab, pure and simple. It targets a small, politically unsympathetic group—high-earning older workers—and increases their immediate tax burden under the guise of financial planning. The logic is paternalistic, assuming savers are incapable of making their own tax-strategy decisions. The implementation is clumsy, creating a scenario where thousands could lose their ability to make catch-up contributions entirely. This is a quiet confiscation of a valuable financial choice, and it sets a troubling precedent for how the government may choose to interfere with retirement savings in the future.